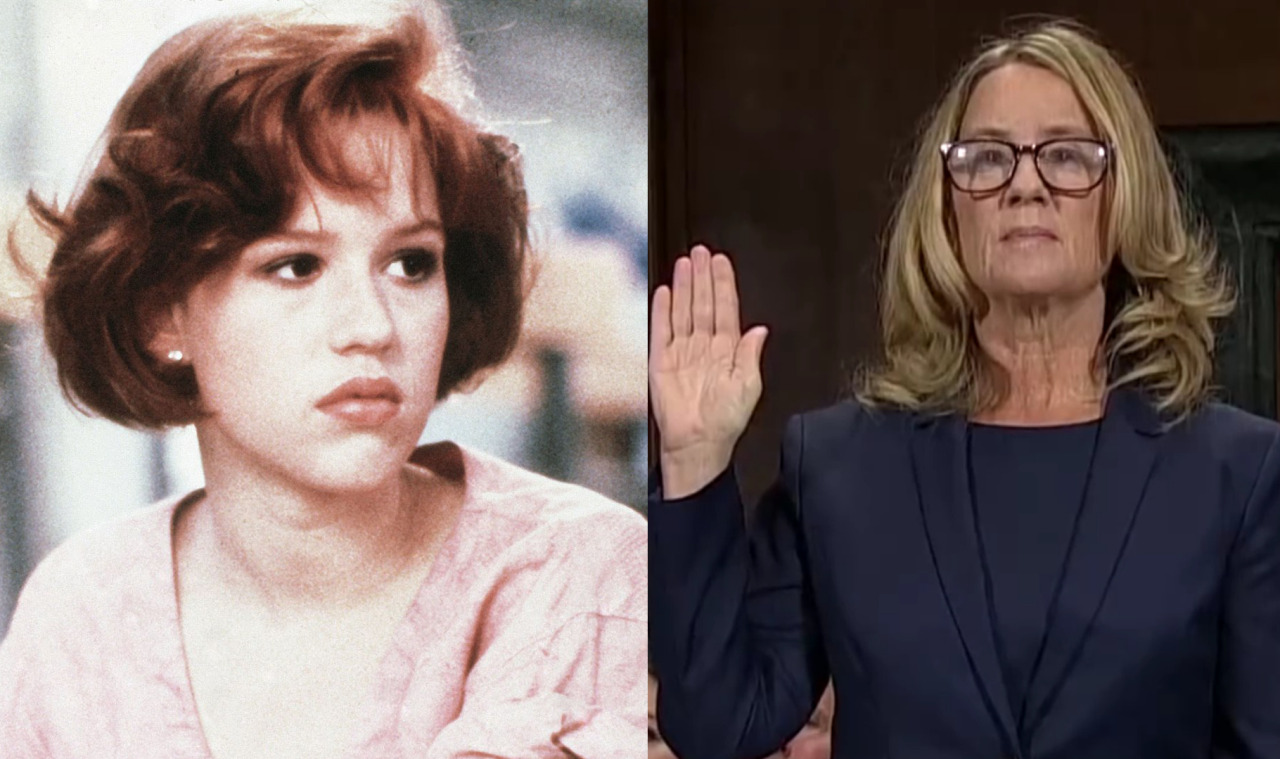

Growing up as a girl in the 80s was no picnic, and I don’t mean because of the big hair and the shoulder pads. It was an era of very confusing messages. On TV, you had Dynasty, Charlie’s Angels and Three’s Company battling with reruns of the Brady Bunch, which meant that the only female empowerment on offer came scantily clad and at some point generally descended into a catfight. The movie landscape was one of Bond girls, bitches, and minimally developed love interests, where we were lucky to get one strong woman main character in some of the blockbusters of the time (Raiders of the Lost Ark, the original Star Wars trilogy – although even Princess Leia was forced to wear a metal bikini), while the movies directed at us teens, like those of John Hughes, combined sympathetic female characters with plot lines that made comedy out of bizarrely awful racial and gender stereotypes (Long Duck Dong, all of the older girls in Sixteen Candles, and almost everything in Weird Science), date rape (what Jake and Farmer Ted did to the prom queen), and sexual assault and harassment (what Bender does to Claire throughout The Breakfast Club) (and if you don’t remember what I’m talking about, read this piece by Molly Ringwald).

This cultural landscape was often reflected back at us in our interactions at school, where my biggest problem, like so many adolescents, was that I always cared way too much what people thought of me — and I never seemed able to get them to think the right things. If I did well in my classes, I got shit for being a nerd. I played lacrosse, but even though I could run, I was too uncoordinated to cradle or shoot well, and got taunted for that. And being a year young, I was always behind in how we were supposed to interact with boys — first we were supposed to be friends with them, then we weren’t, then we were supposed to flirt with them, whatever that meant — and I was mocked for that too. Eventually I developed a fairly crusty shell to help me cope, but it didn’t mean I still didn’t crave the approval of my peers, I just pretended not to. Things weren’t really good for girls who were the opposite of me, though, either. Doing poorly in school made you more popular, which was why a lot of girls played dumb, but then people also made jokes about how dumb you were. Being too good at sports made you too butch and that was unattractive too. And being “good” with boys, of course, made you a slut. In short, everything you were told to be as a girl was a double-edged sword. Sure, if you were socially savvy enough, you could turn any of those negatives around. The easiest way to do that, though, was to pick on some other girl and point out what was wrong with her, usually behind her back — which, if you had any scruples, had its own downside of making you feel like shit. It seemed like your full-time job was to try to walk the very fine line between bitch, geek, butch and slut, never able to find the perfect spot where you could be both liked and respected. Needless to say, I was not a very happy teen.

It was also bad for boys, but the way in which it was bad, and the way that boys achieved, was entirely different. That double-edged sword didn’t exist for them. Although you could be too geeky, you could easily be both a popular boy and a top student — it was even expected. Similarly, there really was no downside to doing well in sports as a boy. You could be called a dumb jock, but if you were a good enough dumb jock, nobody really cared. And success with girls? That was always a plus. No, the hard thing for boys was that they were expected to compete in all of these areas with the other boys, because winning was what earned you both respect and friends. That’s why one of the top put-downs of the era was, “He’s a loser.”

College did end up saving me from much of this. Mainly, I was finally allowed to be smart, I could be athletic without being good at team sports (because the Stanford teams were too good for most high school athletes), and there were plenty of friends to commiserate with over being clueless about guys. What did continue at Stanford, though, as at many schools, was how groups of guys interacted. This was particularly true in fraternities, which just amplified all of these terrible aspects of male bonding (or “male bondage” as one friend of mine aptly called it). That’s why, to this day, we default to the term “frat boys” when talking about a certain kind of male behavior: making everything into a game between them and their pals, where winning and showing off for each other is a central part of male friendship.

A large part of that competition centered around alcohol — which was now easier to access than ever before, particularly at frat parties — and women. With men talking about what “base” they got to and “scoring,” and men the “players” (though okay, that’s really more of a 90s term), could it be any clearer that succeeding with women — which meant getting as close to sex as you could with as many women as you could — was just another thing for them to compete at? And that competition was verbal as well as physical, because even if you couldn’t actually score, you could tell your friends you did, and that was the important thing. Actually connecting with or pleasing women didn’t count for anything with your male friends — or it counted in a negative way and made you p-whipped. In these groups of guys, women weren’t people, we were trophies. If they weren’t trying to compete for us, they were passing us around between them as a gesture of what good pals they were. I can think of several times in my 20s I saw a man trying to get a (drunk) woman who was clearly into him to go home with his friend instead. At least once this meant literally pushing her into a cab with the other guy.

It took me a while to figure out how to deal with this type of man, because they were everywhere in the 80s and early 90s, and their confidence and bravado and popularity with other guys made them attractive to me, in the same way that it made them “winners” in our culture. In college and grad school, I had plenty of male friends who weren’t like that, but it was sometimes hard to tell the difference. Even the frat boys could be decent when you dealt with them one-on-one, and by the same token, when you got practically any group of young men together and added alcohol, even the least fratty among them could get sucked into that macho bullshit group dynamic. I saw it happen constantly, the urge to be one of the guys was that powerful. Plus, because how men interacted in groups of men was how they networked, talking about women was often as important to their careers as talking about sports: if you didn’t know how to do it, guys didn’t relate to or respect you, and you didn’t get ahead. So that two-faced duality, between how they acted with men and how they acted with women, was an accepted aspect of the culture.

This was a huge part of what was so challenging for me entering adulthood, and I’m sure tons of other women like me, who were trying to live and succeed in a male-dominated world: if you knew this was how men interacted with other men, how could you be smart and capable, attractive and sexual, likeable and respected? Often it felt pretty near impossible, and with many men it was — although it took me years to truly get that. I wasted so much time in grad school hanging out with groups of my male peers, feeling like I was accomplishing something by “being one of the guys.” There were some by whom I think I was considered an equal, maybe. But with most of them, it was only after literally years of planning and making films with them, going out drinking with them, listening to them talk for endless hours (because most of them didn’t listen when I talked), that I finally realized that, no matter how much they liked me, I was never going to be one of them. They would never be able to value me the way they valued their male friends/colleagues, and trying to make it so and failing was only making me feel bad about myself.

Having romantic relationships was, if anything, more difficult, because I already knew how all of those guys I hung out with talked about women. When I developed a crush on someone I went to school or worked with, I was always trying to get to a point where I felt sure the guy respected me as a three-dimensional human being before anything happened, so by the time I felt secure enough in that that I was ready to make a move (not that I knew how to do that either without feeling like a slut) the guy had already hooked up with someone else. This happened to me multiple times. In truth, I’ve only had eight sexual partners total in my life, about half of whom were one night stands, and those deliberately so, because when I decided to have sex with someone on a first date, I’d pretty much already made the decision never to see them again. Not because I thought casual sex was wrong, but because it was too complicated for me to have sex with someone and then worry about what they thought about me afterwards, or, worse, said to other guys I knew. It was just easier not to care at all and walk away. Because I knew the odds were that they wouldn’t respect me, and would talk with their guy friends about me, because that was what the groups of guys I knew did. Maybe that’s not true in all industries, but the film business was certainly then, and now in many ways still is, basically a big fraternity. From Polanski to Weinstein to Lauer to Rose to Moonves, if #MeToo hasn’t proven that, it hasn’t proven anything.

So when you wonder why women have fought tooth and nail against Brett Kavanaugh, why we believe his accusers and feel so devastated about the future of women’s rights now that he’s on on the Supreme Court, it’s because we were there. Not in the rooms, necessarily, where he did what he did, but in ones very much like them, with drunk guys exactly like him. And the reason we never reported it? Because everything we saw and heard at the time told us it was normal. I think this is what I find so chilling when Kavanaugh says he’s not guilty of sexual assault: he doesn’t think he is guilty of it, because at the time, none of us got that that’s what it was. We just thought it was something that happened, that women were made to feel culpable for because, after all, we chose to be there, we went to those parties, we drank and hung out with those guys. So no matter how much we hated and were damaged by what we lived through, we just felt like we were expected to let it go — like Ford did, like Ramirez did, even like Julie Swetnick probably did, because even while she’s been dismissed by practically everyone as not credible, we know how guys spiked the punch at parties with something to get women drunk enough to have sex with them all the fucking time. But nobody was going to do anything about it, and if we’d said something we’d have paid a price, either amongst our peers, who would be angry with us for telling, or with authority figures, who would blame us for putting ourselves in those situations, or in our careers, when both of those groups of people wouldn’t want to hire or work with us later on. Plus, knowing those guys and how they think, I’d guess that in Kavanaugh’s mind, what he did wasn’t even really about sex. That’s what you heard in Ford’s testimony: when asked what she remembered most, she said Brett Kavanaugh and his friend Mark Judge laughing “with each other.” For the two of them, it wasn’t about her. It was just two frat boys sharing a good time, the way they always did.

The world is such a different place now than it was in the 80s, but after last week, it feels like women haven’t moved the needle one iota on respect. It’s clear in the way that men still can’t come clean on the stupid and harmful things they did as teenagers 30 years ago, much less the the way they treated women before then, because we all know that as bad as the 80s were, all the decades before that were worse. Even if Grassley, Hatch and Graham never said the word “boof,” the way they won’t listen to us now, the way they claim that we are somehow “mixed up” about things that we know for a fact, the way they still won’t put women in positions of power because they claim that we don’t want to do the work, the way everything they seek to legislate they’re doing for their “fellow man” while ignoring things like control over our bodies, pay parity, and protection under the law from rape, abuse and harassment that women need just to be equal, tells us that they didn’t respect us then, and they still don’t now.

We know how it was. We lived it. And if you’re a woman, you’re still living with it. You feel it in how, even now, decades later, you still have trouble reconciling men and sex and respect, and you probably always will. And if we, as a culture, can’t take responsibility for that, if we still refuse to talk about it honestly, how are we ever going to move forward?