Growing up, my family was firmly upper-middle class. My dad is a lawyer, but up until my college years, he was a public interest lawyer — in other words, not the rich kind. My mother was a teacher, which, again, is a nice, stable job, but not so much a wealth-generator. Still, since they both were children of poor immigrants (my mother grew up in the projects on the Lower East Side and my father’s family were mostly garment workers), and were the first ones in their families to go to college, being white-collar with two incomes was pretty nifty for them. They were able to move their two kids to a nice house in the suburbs, go out to dinner every weekend (my grandmother babysat me and my brother most Saturday nights, which helped), and travel.

Despite this, I think my parents’ childhoods still had a lot to do with how my family spent money. For one thing, once my brother and I were old enough to do road trips, we spent a lot of our summers traveling in Canada — we even made our first cross-country trip across Canada, from Toronto to Vancouver. I’m sure part of this had to do with how great Canada is and how nice it was to be able to travel to another country just a short drive from home, but it also had something to do with the American dollar’s strength against the Canadian: Canada was a bargain. On the other hand, we, like many Americans, spent a large part of our vacations, and recreational time in general, shopping. My father, in particular, is the king of the tchotchke. Any trip into the city would not be complete for him without a stop at the Odd Job Lot and Trading Company, which we all referred to as the Junk Shop, because everything there looked like it had fallen off a truck (and it sort of had). My dad collects lots of things he could look for at the Junk Shop — chess sets, art, kaleidoscopes, unusual musical instruments, lamps — and he loved to discover additional stuff there that one could potentially collect — cast-iron replicas of old banks, ceramics of dubious origin, semi-functional electronics with blinking lights — then figure out somebody to give them to. The key was that, unlike when they were kids, my parents could spend money on stuff that they, or their kids (theoretically), just wanted rather than needed. I say “theoretically” because, even today, as craft fairs, markets, souks and eBay have supplanted the Junk Shop, my folks’ house still has closets filled with “gifts” that are waiting to be given or re-given. Nearly every time I see my dad, he’ll say, “Hey, I have something for you,” at which point he’ll pull out something like a global warming mug on which the continents disappear when you pour in hot water, or a cow keychain that moos and lights up, or a giant piece of folk art designed to take up the better part of a wall. “I thought it was cool,” he’ll say, and if I say thanks but we already have a thousand mugs or we don’t have the wall space, he’ll say, “You sure you don’t want it? Well, maybe your brother/nephew/sister-in-law will like it.”

This idea that money is something you spend on stuff you don’t need had a huge impact on my relationship with it growing up. For a long time, I, too, collected things for the sake of collecting: glass animals, stuffed animals, stickers, books, Intellivision cartridges. Granted, these last two things had value beyond the ability to be collected and in turn collect dust, but the collecting mentality dictated that I acquire all of a given item — every species of animal in stuffed form (armadillo, coati mundi, a watermelon with removable seeds – okay, some of them were really amazing)

every Doonesbury, Garfield, Peanuts, Bloom County, and Calvin & Hobbes collection, every Intellivision game they made. I came to value acquisition, without paying much attention to what things cost. Even when I got an allowance, which I used, like every kid, to buy candy, it didn’t really mean much to me because candy was never in short supply at my house, and my father’s love of shopping meant I could pretty much persuade him to get me anything I wanted. Most of those things were inexpensive when I was little (even newly-released Intellivision games retailed at $39.95 each and quickly dropped in price), so this only started to be problematic when I became a teenager and started wanting things that actually added up to real money, starting with clothes. Buying expensive clothes was a new concept to my parents, for whom appearances in general had never been very important. Clothes, in their minds, were a need, not a want, so why spend money on them? So they initially balked at how much I wanted to spend on my growing collection of sweaters, but since they weren’t used to saying no to me, I eventually got what I wanted.

(Still have a lot of sweaters. Mind you, this doesn’t include the ones in storage.)

Thus, I arrived at college effectively still not really understanding what things cost. My first student bank account was full of money that my parents put into it when I asked, but I rarely needed to ask because I slept and ate in a dormitory and my main source of recreation was parties on campus – a lifestyle for which my parents paid along with my tuition (or so I thought) without my having to think about it. This changed when I began to venture off campus a little more as a sophomore, and so I also, accordingly, acquired my first part-time job at the library for pocket money (which didn’t have to cover the money I spent on clothes at the Stanford Shopping Center, those credit card bills also got paid by my folks). Plus, dorm life in California in the 80s was a great leveler, partly because the uniform of shorts, t-shirts and the occasional sweatshirt could pretty much be worn by everyone year-round, so I wasn’t really aware of who did or did not have money. The hashers who served food in the dining hall were generally work-study, but other clues went right over my head. There was one guy from my sophomore dorm whose class status started to dawn on me when we got into a discussion while party planning about egg nog — he insisted it had to be made with cognac, as anything else would be a crime — and then it all fell into place when I eventually saw his sportscar with tinted windows (although, to be fair, he was from Texas, where tinted windows are much more common than they are in New Jersey). There was another guy who it only became clear that he was from a wealthy family if you visited his dorm room, which was filled with an insane amount of computer hardware for 1988.

My overall obliviousness on the subject of money finally began to erode when I moved to NYC for graduate school. My parents were still paying my rent and most of my expenses, but I had to ask them to send me checks — and while they were happy to do it, I began to realize, thanks to the discussions that would inevitably ensue when the topic came up, that the chunk of change that they sent every month was not nothing. At film school, I also came to know obviously rich people, in the form of classmates whose parents were CEOs or former heads of state. Their money became obvious first in their apartments, which ranged from normal two-bedroom at a stellar address in the Village right near school (which might not seem expensive if you didn’t know New York City real estate) to insane Soho duplex loft space with built-in art installation. Also, while these rich classmates were nice people and I was friends with several of them, it gradually dawned on me that we were not the same. Going out to eat with them, for example, was always hazardous, because many of the places they wanted to go were way out of my league, they never seemed to be aware of how much they spent, and then they’d either want to split the bill, or their guesstimates of how much they owed would be woefully low, or they’d just forget tax and/or tip, or all of the above. I realized, after this happened a few times, that it wasn’t that they were cheap or jerks or cheap jerks, they just literally didn’t understand the concept of money actually mattering. My true rude monetary awakening, however, was receiving my first collection agency notices, from the loan associations in New Jersey, California and Pennsylvania, the three states my parents lived in before and during my college years. My folks had moved twice and hadn’t done a great job of keeping in touch with those agencies, and they’d also never really talked to me about the fact that I’d taken out loans, which someone would eventually have to pay back. So when I started to get nasty letters IN ALL TYPEWRITTEN CAPS telling me that my credit would be ruined forever if I didn’t start sending them money ASAP, I completely freaked out. My parents told me that this was hyperbole and that it would all be fine, and it was (I was able to defer nearly everything until after graduate school), but having to deal with these agencies and consolidate my debt — two truly novel concepts: 1) having debt, and 2) having it be so large that it needed consolidating — was my true initiation into managing my own finances, and into the concept that finances had to be managed, and that mine would have to be managed by me.

As I started working in the film business and paying all my own bills, I evolved into the cheap bastard that I am today, bringing my childhood issues with me. My love of acquisition combined with my inability to resist a bargain made me, for years, helpless in the face of a sample sale, which led to the crazy amount of party clothes I still have in my closet that I never wear and (along with buying a boom pole) my one $4000 credit card bill. On the other hand, thanks to the trauma of my student loan collection agency experiences, I pay my bills in full and on time as a rule (yes, even that one). I also tip well, but have a really hard time doing anything extravagantly. I have friends who have no problem spending large amounts of money on what they deem quality, and I totally understand that, but am physically unable to do it. And just throwing money at a problem to make it go away? I can’t imagine doing that, ever. Paying for something just has to seem worth it to me; the worst epithet that I can throw at something is that it’s OVERPRICED.

Now, when you shack up, your issues with money have to mesh with the money issues of your significant other. For one of my exes, his issues with money involved having the MO of a starving artist while also insisting on being the guy in the relationship, i.e. the one who paid when we went out. As a semi-starving artist myself, I was totally cool with going to divey restaurants, having a cheap apartment even if the walls and ceiling leaked, and acquiring all of our furniture off the street or at flea markets (this was the pre-bedbug era). But the fact that even if I was making a decent amount of money that month he was uncomfortable going out for a nice meal or a weekend away because I was paying for it, that was a problem – as was the fact that he had gotten behind on paying his taxes, another thing I could not fathom ever doing, ever. While those things didn’t break us up exactly, they the reflected larger issues that eventually did: basically, in terms of life goals, I wanted stability, and he wanted to be rich and famous. The relationship that my husband and I each have with money is much more compatible. He doesn’t have the neuroses that I do; he will sometimes tip someone $7 for delivery, and he doesn’t even know if his credit card has an annual fee. I mean, how is that possible? But my slightly neurotic fiscal responsibility is good for him, and his more laid-back generousness is good for me, and if there are still things we have trouble resisting (him: Apple products and synthesizers, me: books and sometimes clothes), neither of us is interested in spending money for the sake of spending money.

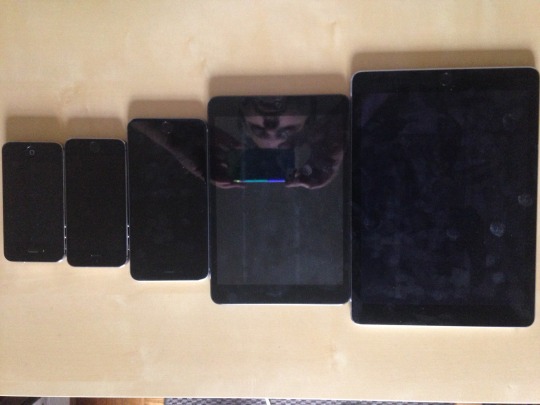

(Damon has a lot of iDevices “for testing.”)

Which is good, because what I’d like is to be able to raise our potential future child(ren) money-healthy — as in they don’t worry about it, or slave for it, or think it’s the most important thing in the world, but they also aren’t oblivious to or ignorant about it and what it can do. I’m not sure if that’s possible to do here in Brooklyn, where you can pay more to buy a studio apartment than it costs to retire, happily, in many parts of the world; in a country where a bargain shopping day (Black Friday) is threatening to wipe out a national holiday (Thanksgiving) and where money has been equated with free speech by the Supreme Court; and in a globalized economy where companies can track every move we make in order to advertise to us individually in everything we read or see or watch or play about the things we MUST MUST MUST BUY BUY BUY.

So be comforted by the idea that, no matter how weird you and I may be about money, the issues we have are nothing compared to the ones our kids are going to have. Yay!