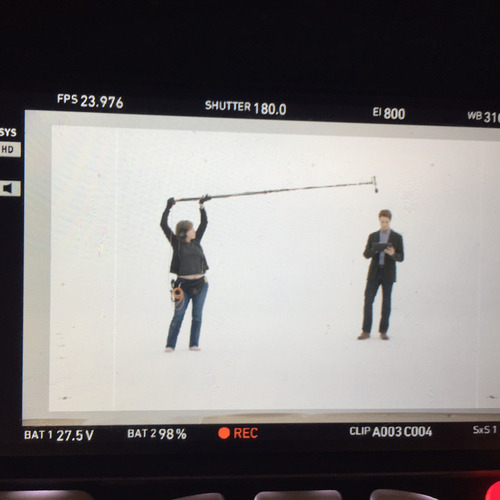

(photo by Matthew Israel)

Recently, my husband was distressed about a video he came across of Louis CK being interviewed at the Paley Center. During the Q&A at the end (around 48:45), CK responds to a question about the best attitude to have in production by saying that people should just be nice human beings, respect everyone else on set, and do the best job they can. He gives an example of a female boom operator on the movie Pootie Tang who was an inexperienced student, who was only on set for a day, and who had brought negativity by being “belligerent,” when she said “Wait a minute, I’m not ready” (which he imitates, comedian style, in an entitled/whiny/let’s-make-fun-of-the-girl voice) when they were trying to roll because “she didn’t like how she had the boom.” This was meant to be an example to all of the students in his audience of what not to do, and Damon was worried that the person at whose expense this snide, cautionary tale was told, was me.

Was it? I don’t actually know. I did work on Pootie Tang, though for a week, not a day, and I do remember running afoul of CK. Once, between takes, I mentioned to him that Jennifer Coolidge, who played the femme fatale, was banging around during a seduction/sex scene with the main character (whose name, yes, was Pootie Tang) in a boiler room, making loud noises over both their dialogue that I thought would be a problem in the edit. Giving these types of notes is something that boom operators are supposed to do, since they are the sound department’s representative on set, and often the fact that there’s a problem like this has to be conveyed quickly, before they roll on the next take. However, I gave him the note in front of Coolidge, and apparently this was a no-no. Often, directors may not judge a technical suggestion about sound important enough to consider when weighed against how applying it might alter an actor’s performance (like asking them to speak up in an intense scene where they are supposed to be whispering), and because some actors are sensitive to any sort of note on their acting, directors can be very protective about what those actors overhear. The sound mixer, as well as the boom operator who had worked on the film before me (I was replacing someone else toward the end of the job), had been informed that this was a rule — not talking about the actors in front of them — but the sound mixer had failed to inform me. I guess my error was bad enough that CK not only came over and told me himself that I should not have done this, but then he also complained to the sound mixer about it — who, rather than defending me by saying, “Oh yeah, I forgot to tell her that you didn’t want us to do that,” basically hung me out to dry by saying, “Well, Friday’s her last day.” (That was the real dick move of that scenario in my opinion, but anyway).

So, I did boom on the job, and CK was clearly aware of my presence on it, and not in a good way. Still, it doesn’t sound like the person he’s describing was me: I wasn’t a student at the time, I was a union boom operator, and I wasn’t only working on the film for one day. However, a student actually couldn’t have boomed on Pootie Tang because it was a union film, so that’s just a red herring, something I guess CK either thought erroneously or thought made the story better, when giving advice to a film student. Plus, if you look at the list of credits at IMDb, you’ll see that there aren’t any women listed in the sound department (there’s a Kelly, but I know him and he’s a guy), which is pretty standard for that time. So it’s kind of unlikely that there were any other female boom ops on the job.

And while I don’t remember the interaction he describes, it’s the kind of thing that has happened to me plenty of times, especially on low-budget movies with first-time directors like Pootie Tang, which tend to be a bit disorganized. For the record, here’s how it’s supposed to work: when the AD calls “Roll sound” on set, everyone is supposed to wait for the sound mixer to roll and tell the boom operator he/she has rolled, at which point the boom op calls out “Speed,” or “Sound speed” (because back in the day, analog, reel-to-reel recorders had to actually come up to speed, or else you’d end up with the first words of the scene sounding chipmunky when you played them back, which generally was not the goal). This has always traditionally happened first, before rolling camera, because rolling camera used to mean, until recently, rolling film, and you didn’t want to start burning the expensive stuff until the last possible second. So the “Speed” call became the cue for the camera assistant to call the slate, at which point camera rolls, slate is clapped, and the director calls “Action.” When people don’t wait for “Speed,” everything can go to hell in a handbasket real fast, because somebody isn’t going to be ready.

Now, part of what sucks about being a sound person is that, because you are the bastard stepchild of set — aka not camera — people don’t bother to check if you’re ready. Not that they should ask necessarily (nobody ever does so we’re used to that), but a good AD should know, because it’s his or her job to be paying attention and observing when everyone on set is ready to go, and only then call “Roll sound.” ADs who are new or overwhelmed, as they often are on low-budget stuff, are not so good at this. That’s why, even if the sound person is rolling, if I’m booming and I’m not ready, I don’t call “Speed” — that’s my (and every other boom operator’s) little secret for how to get just a few extra seconds to get my shit together if necessary. And when you’re working with a low-budge sound mixer, particularly one who is just filling in for someone else, you might need that extra moment because you’re using their equipment, which is often not ready for primetime. The ones I used to work with had boom poles that were used, old, broken or sticky, and they often had no duplex cable – the cable that boom ops used to lay (before almost everyone went wireless boom) from the sound cart to the set every time we went in to boom a shot, to connect the boom mic to the mixing board (you can’t leave the cable in there between set-ups or it gets buried/trampled/destroyed when the camera and lights move). Without it, something kludgy generally had to be rigged, which meant it was harder to put together and put on and get over to set in a hurry. Plus there are the billion other things one might be called on to do right before roll, like adjust a plant mic, or fix an actor’s wire. So, not that I’m making excuses, but…okay, maybe I am making excuses for the fact that when the AD calls roll sound, or the 2nd AC slates, or even when the director calls “Action,” I’m not always ready — and that truly sucks because then I can’t do my job, which is my whole reason for being there, since, you know, it’s my job.

Now these days, when that happens, I’ve been through it so many times that I know how to handle it, and I typically yell out “Stand by for speed,” in my most professional voice, to let people know that I am not ready, and speed has not been called. But back in 2000 when Pootie Tang was filmed, when I had only been booming professionally for six years and in the union for two, when I was struggling to get all of the mixer’s substandard equipment hooked up and over to set, it’s quite possible that I might have responded by instead saying irritatedly, “Wait a minute, I’m not ready.” Because seriously, what the fuck? No matter how I might feel about the material or how disorganized a set is, believe it or not, I still want to do a good job, and not being able to do that makes me feel downright shitty. It may not be my place to show it — in fact, it definitely isn’t — so these days, I generally don’t. But I’m human, and even now, when I’m saying “Stand by for speed,” what I really would like to say is, “I’m not ready!”, or, more precisely, “Hello, morons, can’t you see I’m not fucking ready?!” Which, I’d like to point out, the woman in the story did not say, and I have never said — much as, oh yes, I have been tempted. Because aren’t we all supposed to be on the same team, working toward the same goal, of making this film as good as it can be? And if my job doesn’t matter toward that goal, to the point that you think it’s okay to go on ahead and shoot when I’m not ready, then why the heck am I here?

Again, we don’t know if CK is talking about me, but he is talking about some female boom operator, who he’s making out to be an incompetent student with a bad attitude and a whiny voice, and that’s bad enough. Because as far as I can tell, she’s trying to do her job well – which is exactly what he’s is telling everyone in that audience to do: to care. Maybe, in the heat of the moment, she’s speaking out of frustration, and not in the most professional way, at all. But if you’re saying that everyone should want to work together to do the best job possible, wouldn’t you, as the director, want her to care enough about the fact that she’s not ready to say something, so that she could actually be ready and do her job properly? And shouldn’t you respect her and her work enough to allow her to do that? And, last but not certainly least, isn’t talking about her in a public forum in a disparaging way, using her to make a point and, perhaps more importantly to a comedian, get a laugh, kind of the opposite of treating a person with respect – particularly a woman in a job/industry that already doesn’t treat women with a heck of a lot of it? Because the implication of your story is then really that she should have just shut the fuck up, because yours is the only job, or the only voice, that really matters here. Which is kind of the opposite of the point that you said you started off trying to make.

Sure. Louis CK, like any other director, has his side of things and I have mine, and I can tell mine too. I have this blog that reaches all of, like, twelve people, and even if I didn’t, crew people talk amongst themselves. The stories of a director who is incompetent or an asshole will spread, and likely much more quickly than the stories of the ones who are nice and excel at their jobs, because let’s face it, many of us crew people are aspiring directors and we love to tell tales of the folks who we could be doing it better than, if only we could be doing it. But if you are the director, and have that job that is more important than everyone else’s, the one that everyone wants, and you then become famous for it and get access to a big mic (much bigger than the one I get to hold) with which to tell your story, is this really the story that you want to tell? Does this story make you look like you were in the right, or does it make you look like an ungracious jerk, because you are the fucking director, the person with the power, poking fun at and making an example out of someone who worked for a relative pittance on your movie, and who just, unfortunately for her, cared.

Or maybe that’s just me. Even if it wasn’t.