I’ve had grey hair for at least the past six or seven years now. It shows up in the part on top of my head and in the front, around my temples. I’ve been lucky enough that, up to now, it’s pretty much blended in. My hair is kind of a light brown, but there have always been just enough blond highlights that the grays can kind of hide in there and not be too obvious, for the most part.

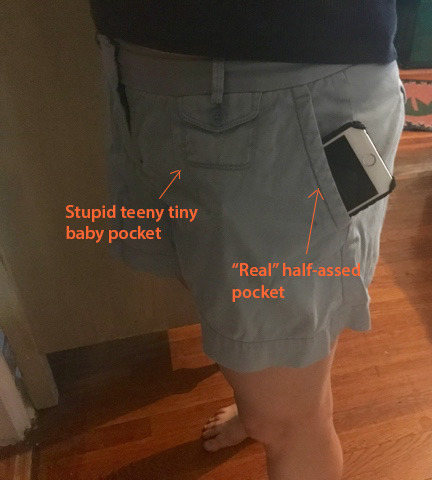

It’s not like I grew up with my hair being perfect or anything — Hahahahahahahahahahahahahahahaha, no. In fact, I was kind of prescient about how much it (and by extension, femininity as a whole) was going to be a trial for me in that I completely refused to deal with it for the first twelve years of my life, allowing my mother to do what she wanted with it when I was little, and then wearing it in pigtails or a ponytail any time I was in public from pretty much second to sixth grade. Sure enough, once I started to pay attention to my hair, I struggled with it endlessly. Like most women I know, I found it to be yet another aspect of my appearance — along with my weight, my height, my nose, the circles under my eyes, my arms, my butt, my stomach, my front teeth…you get the point — that I forever was trying to wrestle into the perfect cultural norm, no matter how that cultural norm changed or conflicted with what it naturally wanted to be. In high school in the late 80s, hair had to be straight or precisely feathered, so my weapons of choice were a blow dryer and one of those round brushes, and, at one point, a curling iron, though I can’t really remember what I did with that other than burn myself. By sophomore year of college, it was supposed to be curly, so I got a perm that I kept through I think senior year, when I finally, at some point, gave in to the fact that my hair didn’t really get curly, even with a perm, it just got wavier. It was the first time it occurred to me that my life would be easier if I tried to work with it rather than against it, so I got a diffuser and tried to just make the waves do something I liked. This principle of just working with what I had (although not the diffuser, which I ditched soon after) became my MO for most of my 20s and 30s. It justified doing very little when I was going to work on set at 6 am, when I both didn’t want to attract attention to the fact that I was female and didn’t want to get up any earlier, and made it possible to go for a certain kind of wavy bigness when I went out that I deemed its most positive result, by using mousse, gel, spray, scrunching, finger-wrapping, blowdrying upside down, and whatever other techniques I saw or heard about other people using (I didn’t actually spend money on fashion magazines because fuck that scam, but I still queried my friends and hairdressers). At the same time, I was so obsessed with the obsession hair can be for women (and for some men) that I made my first documentary about it, exploring the connection it forms for many of us between appearance and identity.

Which of course led to me to deconstruct how my hair related to my identity even more, and some time in my late 30s, I entered my most recent stage of hair “care”: the stage of not caring. I stopped blowdrying my hair altogether, except in the winter, if I had to prevent it from freezing, then I basically stopped using product when I went traveling for weeks on end in Latin America and having it meant just having one more thing to carry. I did still want to attract people, because I was still single, so I would make an effort to do something with it if I was going out or had a date, but once I met my husband at age 40, that was pretty much the end of even that. In the past year or two, my intricate, personal hair ritual has become washing it every other day (this was a concession to the drying effect of the grays, but it also fit in nicely with my growing feelings of apathy), brushing it upside down (somehow that just stuck, even though I don’t think it does anything if you don’t use product) and then going right-side-up and making sure there’s something of a part. That’s it, and it takes all of maybe eight minutes, including the washing part — without that, it takes two. And that has seemed about right for a while now. On set, my job is really just to blend in, so I basically have to look just well-kept enough that nobody will think there’s something something seriously wrong with me, at least not in any way that would be distracting to the actors. So, yeah, that’s what I ask of my hair: just don’t make me look crazy. I do still have several bottles and tubes of product that I’ve acquired over the years, so when I’ve got to go to a wedding or a bar mitzvah or something, I might roll the dice and use one of those, even if it’s expired. But in general I’ve felt like, given all of the other things going on in my life, this was expending about as much energy toward my hair as it deserved, and so I had to be okay with the results. Even when I saw pictures of myself later on and wasn’t all that thrilled, that’s hardly a new experience for me, considering how, as you might have guessed, I have never developed an attractive look to present in photographs. Want examples? Of course you do. Here, here, here (based on how often I have my eyes closed and my mouth open in photos, I must both blink and talk more than other people), here (granted, it doesn’t help when someone is squishing your face — I doubt a Kardashian would ever allow that), and here (yes, I’ve just reached the top of Machu Picchu, and still I don’t look happy).

A couple of months ago, though, something felt like it changed — or maybe it was a combination of things. For one, I got a less good haircut than usual. Again, I have nobody to blame for this but myself, since I get my $35 haircuts from a local hairdresser that seems to be popular more as a barbershop-like neighborhood hangout than as a consistent, up-to-trend stylist, and I often don’t pay attention to what’s being done. This last time I was exhausted from work and so I was literally asleep at the wheel — I kind of knew she was parting it too close to the middle, but eh. For another, I bought a different shampoo than the one I’ve been using for maybe ten years plus, since they were out of it at the Park Slope Food Coop — again, my fault for relying upon the Park Slope Food Coop to be consistent with their stocking, and for choosing instead to try a “thickening shampoo” even though my hair isn’t thinning, because eh.

But honestly, I think the real culprit is just the gray. It’s reached a critical mass that can’t really be ignored any more — not so much the color, as what it’s doing to the texture. It’s wiry. It doesn’t behave. It looks messy and dirty, and in a way that no hipster could pretend was intentional. It looks bad.

When I realized this, I took an informal poll of my friends about their hair. Which means, I was at a wedding with my high school friends, and then a get-together with my college friends, and then looking at photos sent by my other college friends. And the upshot was, basically, everybody dyes. Out of all of my female friends who are at the age when I know that they must have gray hair by now, I seem to have only two who actually do.

That’s pretty crazy. I guess I was kind of hoping that by the time I got to be this age, we’d have all of this shit worked out already. I just thought we were going to take that final step forward and be the generation of feminists who were allowed to get old, who could truly accept ourselves for who we are rather than how society expects us to be – forever young and thin – and be valued for the wisdom, experience and skill that make us distinguished, the way we think of older men, rather than extinguished. When I looked at my friends on an individual basis and noticed they were dying their hair, I told myself, Well, she’s always been very pretty and it’s hard to let go of that, or, She works in an industry that’s very competitive, or, She’s someone who is very in control and it’s just another a way of expressing that, or, Well, she lives in Texas. But as I started to get more uncomfortable with the changes to my own appearance as I got older, I started to realize, No, this getting old shit is just hard, and it doesn’t really get easier, no matter how enlightened you may tell yourself you are. It’s kind of just one new hurdle after another, as one more aspect of your appearance starts to go. Now that it’s my hair that isn’t looking good to me, the idea of dying doesn’t seem so unthinkable. So maybe it wasn’t ever that I was more feminist, or less vain, or less…Texan than they were. Maybe I was just lucky.

I’m of two minds about this. On the one hand, you’re not supposed to surrender your principles when they become inconvenient for you. In this political moment, that seems more important than ever. On the other hand, couldn’t I just fucking go easy on myself for once? Rather than trying to pretend that I don’t care about getting old, because I don’t want to care, shouldn’t I be entitled to whatever is going to make that process slightly less sucky? It’s hard enough having more people noticeably ignore you, knowing that means not only that the world doesn’t any longer think of you as attractive, but also doesn’t think of you period – meaning you’re far more likely to fail, not just because you’re old and you have less time, but because people will give you far fewer opportunities than you had when you were younger. Why shouldn’t I be allowed to do anything that continues to give me more of a fighting chance? But then my other mind comes back with, But where does that end? Am I going to decide that I next need Botox to make myself happy, or a full-on facelift, if that’s what my friends are doing? I know some people probably don’t see this as a continuum, but I can’t help it. Once you surrender to what society thinks you should be, rather than what you believe about yourself or aspire to be, where does it end? Am I going to be the friend who makes it okay for someone else to get a tummy tuck, because they tell themselves, “Well, Betsy did it, and she’s a feminist, so…”

These are hard questions to answer, and so I’ve chosen…spray-in conditioner. It’s helping to make my hair be less dry and unruly — in other words, it continues to make the gray continue to blend in. Is that on the continuum? I suppose that it is. If I really wanted to make the statement that women should be allowed to go gray, I’d just do nothing and let it be that way in all of its unruly glory. But I guess the personal compromise I’ve learned to make between the social norms of beauty, and feminism, and my identity therein, is to work with what I have — not trying to “fix” myself, but not ignoring wholesale what the world thinks either. Because you can’t. It’s in your head, it just is.

So I’m not here to judge how you do it — every woman has to figure out how to walk that line for herself. But I can also still dream of the day we won’t have to any more, can’t I?